work

Feb 4, 2026

The Taste Deficit, Part II

Why AI Can't Bottle Your Vibe

10 min

read

Summary

AI lacks subjective taste, relying on data patterns rather than human intuition or emotion. While AI enhances productivity, true creativity requires an author’s unique vibe and lived experience. Humans provide the authenticity and spirit that machines cannot replicate.

Consider the creative process in general: the artist reaches deep into the mysterious, infinite well of possibility, plucking an idea to be shaped from the void. Soul alight and charged by an awakening energy, we try to capture lightning in a bottle, the prism of our perspective emitting a unique rainbow of shades as we express it. We are enlivened.

This is not at all what AI is doing when it generates content. It's simply weighing the value of the next best word, pixel, or note against a giant corpus of human output that it has seen before, including the prompt instructing it as to what should be done. This may seem to some like the same thing an artist is doing, but it's different chiefly because of pervasive role of subjective taste.

In Part I of this series, we discussed the role of taste in both the conception of an idea, and throughout the production process. We left the elephant stomping about in the room, though: will human beings be needed to express their taste within commercial processes, or will AI commoditize that as well? Note that this is not the same as asking "can an agent produce something good on its own?" This is more a question of whether or not AI can fully express your taste on your behalf. What level of our involvement is required?

To try to answer that, here we'll explore some examples of the use of AI in the creation of music and text, to help understand the need for taste throughout the production process.

Vibe check fail

When you try to get an LLM to express taste, or more likely you forget to express your own when asking it to do something for you, it will almost never give you what you want, and it will regularly have you wondering how it could have thought that was appropriate for the task at hand. AI is excellent at providing a list of potential directions based on what came before — which isn't surprising, because it has "seen" much more than you have. But it's terrible at selecting the "best" direction. What is "best" is an expression of our aesthetic — how we feel about it. It doesn't seem that robots have an aesthetic (yet), or how that would even jibe with our own even if they did, since their neural nets and "lived experience" are quite different from ours.

I formed these opinions somewhat inadvertently while writing this article. I wanted to generate some background music for the voiceover, so I made an attempt to describe the "vibe" I was looking for, to Suno. Here was my prompt:

Me: Backing track for a voiceover of a blog article called "The Taste Deficit." Should be cool, stylish, and inspirational, with forward movement, and evoking contemplation, without distracting from the read-through. The instrumental melody should feel improvised and should vary throughout. There should be a bridge section for interest.

I didn't like all of the ideas it came up with, but thought one you're listening to right now (on the voiceover) might be good enough. But then I paused and thought to myself that perhaps the prompt itself could have been better generated using my article's text as input, the thinking being that AI could more quickly consider the tone and themes from my article and form it into a prompt, which Suno could then itself use to generate suitable music. So instead I created this more self-referential meta-level prompt:

Me: Create a prompt for a music generation system from which a backing track for the voiceover of this article can then be generated.

Here's the prompt my notebook came up with:

NotebookLM: A minimalist ambient track blending steady electronic pulses (robotic productivity) with expressive, 'impressionistic' piano melodies (human taste). The music should feel like 'meandering experimentation,' evolving from rigid structure into fluid, intuitive patterns to reflect the 'magic' of human craftsmanship. High-fidelity, philosophical, and sophisticated.

From this, Suno produced this music (played on the voiceover).

A few things can be noted here. The generated prompt was a much better attempt at mapping the content of my article into a matching prompt, as opposed to mine, which was a more generic statement about how I wanted the backing track to feel. Also, Suno followed both prompts fairly well, especially given how little was supplied as context. But the track that it produced from the Notebook prompt wasn't what I was looking for. In my view, it might have been better suited to the soundtrack for a sci-fi film. I just liked the results from my prompt better than those from the generated prompt.

generated by deepai.org

<let's get back to the original music.. ahh that's better.>

Reflecting on why this happened, I realized that I had an intended vibe for the backing tracks from my article, even if this wasn't apparently implied from its content. And there was no way for the chatbot to know that. Since the chatbot had no feelings, it made a "best guess" based on semantic analysis of my article text, but headed down the "wrong" path.

In my attempt to "go meta" with the AI generation of an AI prompt, I had inadvertently excised the important step where I injected my taste. While Suno can generate a reasonable tune approximating the intended tone from the instructions I give it, it can't know what that tone is unless I tell it, and even then it can't really have a feeling as to what it "should be."

It's also important to note that my opinion is the one that matters at the point of creation, since the article isn't meant to have a specific utility for a target audience; I'm writing first for myself. I do understand that readers will inject themselves into any text, and will likely add personal thoughts that I didn't have to the narrative, which is perfectly valid. They'd likely have made different musical choices, too. Hell, on a different day I would have made different choices.

But this experiment reminded me that I get much better results by first focusing on clarity of intent: distilling and expressing the intended vibe to myself, which is what the creative process is all about.

Words need a pulse

When producing text, AI knows how to organize and research a vast range of facts and ideas, has more extensive context, and can produce an organized narrative better than most humans. So why go through the rigamarole of making it "sound human" or "sound like me," or more to the point, of writing it at all? This writer, for example, aims to provide the AI explicit instructions about how to sound "more human," and more "like him/her," presumably to claim authorship afterward. Notwithstanding the potential for deceit, this begs the question "what really is the point of the human being in the writing process?"

I challenged an AI with this very question, and its obvious answer had me feeling a bit embarrassed for having asked. Basically, "you get out what you put in" and "shouldn't an article about taste be an expression of and by the author?" Ahem. Yes, of course.

Furthermore, even as we surrender productivity to AI, we can't forget to continue to develop our minds and remain engaged with the world. Taste is cultivated with curiosity, play, and exploration over time. Outsourcing this activity eventually means losing our very ability to do it. I'm having WALL-E nightmares of what would become of us then!

Also, while capitalism teaches us that the product is the point, this is only part of the story. Indeed, I often end up a writing a completely different piece than the one I intended to write at the start. Each article is a journey of a kind .The output is just a momentary snapshot of the words that happened to spill out at the time, and to which I responded positively. A reflexive process — inseparable from my intrinsic aesthetic — rules.

While AI offers efficiency, structure, clarity, and (if we're lucky) objectivity, humans offer authenticity, credibility, connection, and taste, not to mention two other ethereal, tantalizing outcomes for the creator: aliveness and satisfaction.

This is to say nothing of the fact that our subjective response to that output is also distinctly human. Feelings can't be directly grafted onto robots. You can ask a robot to bake some garlic bread, but not if it likes the taste. AI already knows this, and so should we. AI may, in time, develop its own subjective experience, which of course will also be foreign to us. But human feelings are thoroughly intangible and largely inexpressible, even to one another. Who among us can begin to understand the alchemy of poetic fusion that occurs between artist and audience?

So I no longer wonder if I should continue writing these essays myself. I write them because I want to be a player on the field of creativity; I'm trying to grow as a writer, understand my own mind, and test for echo with yours. I'm after improvement through struggle, satisfaction, self-expression, and human connection, none of which I can get if I farm it out to AI. In addition, there would likely be a painful aesthetic mismatch between my intention and what AI produces. To be creative is to be human. Words need a pulse. The creative process will remain largely within the purview of the human family if it is to continue to have any value to us at all.

It all comes down to taste

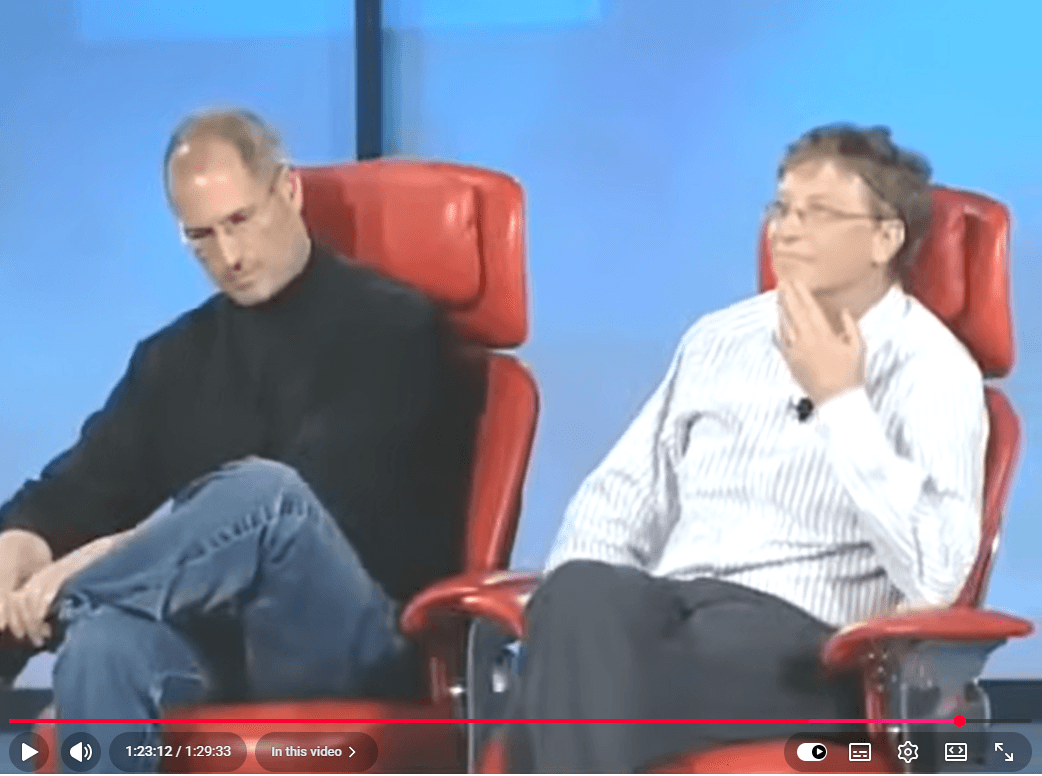

Two of the titans of the tech world understood deeply the importance of taste. A 2007 interview with Bill Gates and Steve Jobs had them reflecting on their careers. During the question and answer portion, Bill mused (with atypical vulnerability) about Steve's taste.

Audience Member: You approached the same opportunity so very differently. What did you learn about running your own businesses that you wished you'd have thought of sooner, or thought of first, by watching the other guy?"

Gates: I'd give a lot to have Steve's taste. He has natural (not a joke at all) I think in terms of intuitive taste both for people and products... we sat in Mac product reviews, where there were questions about software choices, how things would be done, that I viewed as an engineering question... that's just how my mind works. And I'd see Steve make the decision based on a sense of people and product, that you know, is even hard for me to explain. The way he does things is just different. And you know, I think it's magical.

— Steve Jobs and Bill Gates at D5 Conference 2007

This is was a long-delayed public response to comments Steve made in the "lost interview" about Microsoft having no taste (for which he later apologized to Bill privately for having said it publicly, notwithstanding the fact that it was his belief at the time). I'll continue to quote extensively from this interview, since much of it is very relevant to our topic.

Jobs: The only problem with Microsoft is they just have no taste. They have absolutely no taste. And what that means is... I don’t mean that in a small way, I mean that in a big way. In the sense that… they don’t think of original ideas and they don’t bring much culture into their product. And you say, “Well, why is that important?” Well, proportionally-spaced fonts come from typesetting and beautiful books. That’s where one gets the idea. If it weren’t for the Mac, they would never have that in their products. And so, I guess I am saddened, not by Microsoft’s success. I have no problem with their success. They’ve earned their success for the most part. I have a problem with the fact that they just make really third-rate products. Their products have no spirit to them. Their products have no spirit of enlightenment about them. They are very pedestrian. And the sad part is that most customers don’t have a lot of that spirit either. But the way that we’re going to ratchet up our species is to take the best and to spread it around to everybody, so that everybody grows up with better things and starts to understand the subtlety of these better things. And Microsoft’s just... it’s McDonald’s. So that’s what saddens me. Not that Microsoft has won, but that Microsoft’s products don’t display… more insight and more creativity.

— American journalist Robert X. Cringely's "Lost Interview" with Steve Jobs, 1995

Listening to that passage again, I realized that I'd almost missed the phrase "And the sad part is that most customers don’t have a lot of that spirit either." Notions of value are quite malleable, and Jobs was a tastemaker. Not only did he have strong aesthetic opinions, but his advanced rhetoric regularly helped moved millions of people to feel a kinship with the Apple brand. Jobs' legendary and often magical product launches focused on "showing us better things," fanning the flames of our collective iDesires. What is striking, though, isn't just Jobs' taste, but the fact that he was able to make nuanced, intuitive judgments about what would resonate with people before they even knew themselves. This kind of anticipatory empathy may require not just pattern recognition, but an acute attention to the lived experience of being human.

"Taste" has both individual and universal dimensions. No-one has the particular mix of your exact genetic makeup, cultural context, life experience, and perspective that you have. But we are all part of a family of billions with patterns of similarity baked right into our genes, giving us ten fingers and ten toes, and a structurally similar brain with which to wiggle them. Said another way, "taste" is an expression of both what you value personally, and what we all value as human beings. Without it, Jobs says, we produce pedestrian things.

Tool of the century

During the same interview, Steve makes comments on being lucky enough to find himself at exactly the right place and time to witness the birth of the personal computer revolution. He also relates this to the importance of taste in guiding that revolution, calling the personal computer the "bicycle for the mind." Read the next passage closely, though, and imagine instead that he's talking about "AI," instead of the personal computer — his analysis is still eerily applicable. Could AI be a sort of "telescope of synthesis," augmenting our own minds with the creative output of all who have come before us, putting us on roads never before travelled, and allowing us to peer further and deeper into the galaxies of our own curiosity?

Jobs: I read an article when I was very young in Scientific American, and it measured the efficiency of locomotion for various species on the planet. So for bears and chimpanzees and raccoons and birds and fish. How many kilocalories per kilometer did they spend to move? And humans were measured, too. And the condor won. It was the most efficient. And mankind, the crown of creation, came in with a rather unimpressive showing about a third of the way down the list.

But somebody there had the brilliance to test a human riding a bicycle. Blew away the condor. All the way off the charts. And I remember, this really had an impact on me. I really remember this that humans are tool builders, and we build tools that can dramatically amplify our innate human abilities. And to me... we actually ran an ad like this very early at Apple. The personal computer was the bicycle of the mind. And I believe that with every bone in my body that of all the inventions of humans, the computer is going to rank near, if not at, the top as history unfolds and we look back. And it is the most awesome tool that we have ever invented, and I feel incredibly lucky to be at exactly the right place in Silicon Valley, at exactly the right time, historically, where this invention has taken form.

And as you know, when you set a vector off in space, if you can change its direction a little bit at the beginning, it’s dramatic when it gets a few miles out in space. I feel we are still, really, at the beginning of that vector. And if we can nudge it in the right directions, it will be a much better thing as it progresses on. I think we’ve had a chance to do that a few times, and it brings all of us associated with it tremendous satisfaction.

Cringely: But how do you know what's the right direction?

Jobs: You know, ultimately it comes down to taste. It comes down to taste. It's... it comes down to trying to expose yourself to the best things that humans have done and then to try to bring those things in to what you're doing. I mean Picasso had a saying, he said "good artists copy, great artists steal." And you know, we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas. And I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians, and poets, and artists, and zoologists, and historians who also happen to be the best computer scientists in the world. But if it hadn't been for computer science, these people would have all been, you know, doing amazing things in life in other fields. And they brought with them... we all brought to this effort a very liberal arts.. sort of... air... a very liberal arts attitude that we wanted to pull in the best that we saw in these other fields into this field. And I don't think you get that if you're very narrow.

— American journalist Robert X. Cringely's "Lost Interview" with Steve Jobs, 1995

From productivity to purpose

AI systems may still be able to simulate certain aspects of taste convincingly, even if they don't truly "have" it, because we continuously infuse our humanity into its output by judging it. Taste requires a conscious, embodied experience. Our taste paired with the array of possibilities provided by AI may be enough for practical purposes, depending on the application. And of course, if taste is an emergent property of the human experience, then it may also eventually emerge for robots.

At least for now, human beings are the primary consumers of AI output, inoculating "taste" from an automation attack. Creative output must resonate intuitively and emotionally with us before we find it valuable. Great content bridges seemingly unrelated aspects of the evolving human experience, and can only be understood from a lifetime of being uniquely, messily human.

Whether or not we remain resilient to replacement in an economic sense matters less than the potential to more fully project ourselves into the world, and the enjoyment of the subjective experience of being alive. If AI systems obsolete our productive value, but help bring forth this outcome, then... good trade!

Here's one final word from Steve Jobs, about being more of a "hippie" than a "nerd."

Cringeley: One of the questions I asked everyone in the series was,” Are you a hippie or a nerd?”

Jobs: Oh, if I had to pick one of I’m clearly a hippie. All the people I worked with were clearly in that category, too.

Cringeley: Really? Why? Do you seek out hippies, or are they attracted to you?

Jobs: Well, ask yourself, “What is a hippie?” I mean this is an old word that has a lot of connotations, but to me, ‘cause I grew up… remember that the ’60s happened in the early ’70s, right? So we have to remember that. And that’s sort of when I came of age, so I saw a lot of this. And a lot of it happened right in our backyard here. So, to me, the spark of that was that there was something beyond sort of what you see every day. There is something going on here in life... Beyond just a job, and a family, and two cars in the garage, a career. and there is something more going on. There is another side of the coin that we don’t talk about much, and we experience it when there’s gaps, when we just aren’t really... when everything is not ordered and perfect, when there is kind of a gap, you experience this inrush of something. And a lot of people have set off throughout history, to find out what that was. Whether it’s Thoreau, or whether it’s some Indian mystics, or whoever it might be, and the hippie movement got a little bit of that, and they wanted to find out what that was about, and that life wasn’t about what they saw their parents doing. And of course, the pendulum swung too far the other way, and it was crazy, but there was a germ of something there. And it’s the same thing that causes people to wanna be poets instead of bankers. you know? And I think that’s a wonderful thing. And I think that that same spirit can be put into products, and those products can be manufactured and given to people, and they can sense that spirit. I mean, if you talk to people that use the Macintosh, they love it. You don’t hear people loving products very often. You know really. But you could feel it in there. There was something really wonderful there. So, I don’t think that most of the really best people that I’ve worked with have worked with computers for the sake of working with computers. They’ve worked with computers because they are the medium that is best capable of transmitting some feeling that you have, that you want to share with other people.

— American journalist Robert X. Cringely's "Lost Interview" with Steve Jobs, 1995

In our context, "that feeling you have and want to share" is an expression of your taste, or in a larger sense, your essence; that thing that makes you, you. Jobs viewed hippies as a movement of people searching for that experience of "something exciting beyond the job"... that sense of the curious, mysterious, or beautiful. Robots may well help us get there by unburdening us from the need for productivity. It's an open question as to whether they get there themselves, but regardless, how exciting it would be to live more fully and with purpose, focused on the discovery and full expression of our essential selves; our cosmic, magical essence.

————————————————————————————————

Text written and spoken by Jeremy Chan — a human being!

Voiceover background music by Suno

AI Podcast by NotebookLM, with intro / outro Music from #Uppbeat

https://uppbeat.io/t/soundroll/stronger-every-day

License code: TW15Y0RDUQ16MUQY