philosophy

Jan 14, 2026

The Value Delusion

How "Value" is a Ghost in the Machine of the Mind

13 min

read

Summary

What is at the root of the things we value? Using the "5 Whys" technique and by relating our lives to other things we think are valuable (gold, real estate, art, stocks, crypto, etc), we begin to see that value often lacks objective foundations. Instead, it is a subjective construct manufactured through marketing, cultural conditioning, and perceived scarcity. Ultimately, value depends on shared human beliefs and tribal psychology, serving as a proxy for meaning in an otherwise abstract and uncertain world.

Article Voiceover

AI Reaction Audio

Having recently retired, I'm preparing for a financial reality in which money leaves the bank account and isn't replenished, which is a bit unnerving. So I started to ruminate a bit more on how I'll budget for my life, and further what indeed is valuable to me and why, so that I can make better decisions about where to place my bets. But in thinking on this, it occurred to me that "value" is a slippery and elusive thing.

The same thing can be valued differently by different people. One might then say that "it's valuable if it is useful to someone," but then you have to define why something is useful. "Because it gives you something you want" isn't good enough, because sometimes the things we want are bad for us. Also, sometimes utility isn't the goal: things with sentimental value may not have any use, but they give us a "good feeling." Perhaps you then shift to "valuable things make me feel good," but the hours spent practicing the guitar don't necessarily make me feel good in the moment; it's the long-term results associated with consistent practice that eventually make you feel good. In the moment, it actually feels kinda crappy.

One might say that food and shelter are valuable because they help us to stay alive, but that presupposes that life is inherently valuable. This seems obvious until you contemplate it more deeply:

we take the lives of other living things to preserve our own

some take their own lives to escape the pain of living

throughout history, peoples have enslaved other peoples, ruining their lives in the name of productivity and wealth

the horrors of war and ethnic cleansing cast shadows on the idea of the "sanctity" of human life

capital punishment is an outcome of the thinking that some no longer have a right to life based on their actions, which might themselves have included taking someone else's life

At best, it seems we can only say that my life is more valuable than yours, right now.... which of course can't be true for everyone at the same time. Weak sauce.

Sometimes I even have difficulty figuring out why life is valuable to me. There's something about not wanting to miss out on experiences, perhaps... It definitely feels like I want to be alive, but I don't really know why. It might just come down to my genes trying to replicate themselves using the host cells' machinery, like a virus. I bet viruses don't even enjoy all the havoc that they cause…

So what tools do we have to help untangle the reasons why things are valuable?

Down the rabbit hole

The "5 Whys" is a problem-solving technique developed by Toyota founder Sakichi Toyoda, which involves asking "why" five times in succession to drill down to the root cause of some problem or phenomenon. By the end of that exercise, Toyoda posited, you would have reached the "fundamental" cause.

For example:

Problem: The car won't start

Why? The battery is dead

Why? The alternator isn't working

Why? The alternator belt is broken

Why? It exceeded its service life and wasn't replaced

Why? There's no preventive maintenance schedule

The technique reveals how surface-level explanations often mask deeper, more fundamental issues. It should be pretty clear, though, that "five" is an arbitrary number. You can just... keep going forever. "Why was there no preventive maintenance schedule? Because we didn't have enough data to know when the belt would likely fail. Why didn't we have that?" etc.

Louis CK hilariously quipped about the futility of trying to satisfy the incessant "whys” of his infinitely curious kids, something all parents are familiar with.

Louis CK on kids questions

You can't answer a kid's question. They don't accept any answer! A kid never goes "oh thanks I get it" they fuckin' never say that! They just keep coming... more questions why why why till you don't even know who the fuck you are anymore! At the end of the conversation it's an insane deconstruction it's amaz... this is my daughter the other day she's like

Papa why can't we go outside?

Well cuz it's raining.

Why?

Well... water's coming out of the sky.

Why?

Because it was in a cloud.

Why?

Well, clouds form when there's vapour...

Why?

I don't know. I don't know! that's... I don't know any more things. Those are all the things I know.

Why?

Cuz I'm stupid okay? I'm stupid.

Why?

Well, because I didn't pay attention in school okay I went to school but I didn't listen in class.

Why?

Cuz I was high all the time. I smoked too much pot.

Why?

Cuz my parents gave me no guidance they didn't give a fuck!

Why?

Cuz they fucked in a car and had me and they resented me for taking their youth.

Why?

Because they had bad morals. They just had no compass.

Why?

Cuz they had shitty parents! It just keeps going like that!

Why?

Cuz fuck it we're alone in the universe nobody gives a shit about us! I'm going to stop here to be polite to you for a second but this goes on for hours and hours and it gets so weird and abstract at the end it's like

Why?

Well because some things are and some things are not!

Why?

Well because things that are not can't be!

Why?

Because then nothing wouldn't be! You can't have fuckin nothing isn't! Everything is.

Why?

Cuz if nothing wasn't there'd be fuckin all kinds of shit that we don't... like giant ants with top hats dancing around. There's no room for all that shit.

Why?

Aww fuck you eat your French fries you little shit! God damn it!

— Louis CK

Besides being generally frustrating, the infinite whys problem exposes how our reasoning often rests on surprisingly shaky foundations. The more you contemplate the question "why is thing X valuable?" and iterate on successive whys, the more abstract and ethereal your reasons become until your rock solid beliefs have disappeared altogether, leaving you holding the empty bag in which you could have sworn you were carrying them [1].

Existential inquiries lead some to find God at the end of their list of whys, satisfied that the mysterious inner workings of the mind of the big man himself are not for us to understand, but instead to trust. Faith (in God) is the feature that allows the faithful to put that kid to sleep at night. But that doesn't really help the rest of us...

If the infinite whys leave us on shaky ground, perhaps we can discover the roots of value by analogy with other valuable things?

Solid gold

Photo by Jingming Pan on Unsplash

Gold is the OG store of value. It's relatively durable (doesn't tarnish, or evaporate at room temperature), somewhat fungible, and generally acceptable as payment, which are three important aspects of a value store. But I'll bet you can't even remember where the notion that "gold is valuable" was parked in your psyche. We all seem to believe it, or at least accept it as a useful baseline proposition.

But parked it was. Our language and culture are so saturated with references to gold as a standard for excellence, purity, and value that we often use them without realizing we are implicitly reinforcing gold’s status as the king of metals.

"The gold standard" and "gold medals" represent the pinnacle of excellence. "The golden rule" and "heart of gold" are metaphors for unimpeachable character. "The Midas touch" and "the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow" provide mythological support. "As good as gold" and "worth its weight in gold" are idioms of worth and scarcity. And filmmakers and revelers all know that the the "golden hour" is when the light is soft, warm, and rich.

Gold first became valuable in ancient Egypt, around 2600 BCE, where it was used for jewelry, ceremonial objects, and in the creation of divine symbols. One might understand that the non-corrosive, shiny properties of gold might have helped to cement its utility in these use cases, but in them modern age there are many such materials, making gold much less unique in this regard. Despite this, gold's perceived value has persisted through the years.

Cultural conditioning is at the base of gold's value pyramid. Because of this, gold neither requires a governmental stamp of approval, nor even the existence of a government, to be seen as valuable. Interestingly, though, when the price of gold goes up beyond the price of extraction, mining companies (today's gold rush prospectors) simply unearth more of it, regulating both its supply and its price. This casts doubt on whether it really is as rare as we think it is, in practical terms. But sure, it does take a lot of energy to get it out of the ground.

We agree with the Egyptians that gold has value because it's pretty when worn as jewelry, and it does have properties in industrial processes that allow us to create things like high-end headphones. But the vast majority of the mined gold in the world is sitting in highly secured vaults, with fractional ownership assigned on some ledger. At its core, gold is mostly just a shiny metal that we dig up, purify, form into bars, and store in vaults so that we can point to it, proclaim that we have it, and somehow be assured that at a later date others will accept it as payment for stuff, who then in turn store it in another vault.

Most of the time when we use gold to pay for things, we don't even bother moving it, since it's hard to move around and divide. To help with this, the Bretton Woods system was established after World War II, which had nations around the world agreeing that their individual currencies could at any time be converted to US dollars, and that dollars could be converted to gold at a known price (USD $35 per ounce), allowing everyone to use the dollar as a global trading standard backed by gold.

As weird and recursive as all this sounds, as a global family we had largely adopted gold as the primary economic "battery" that both fueled the engine of productivity, and stored its output for later use.

The (empty) promise of paper

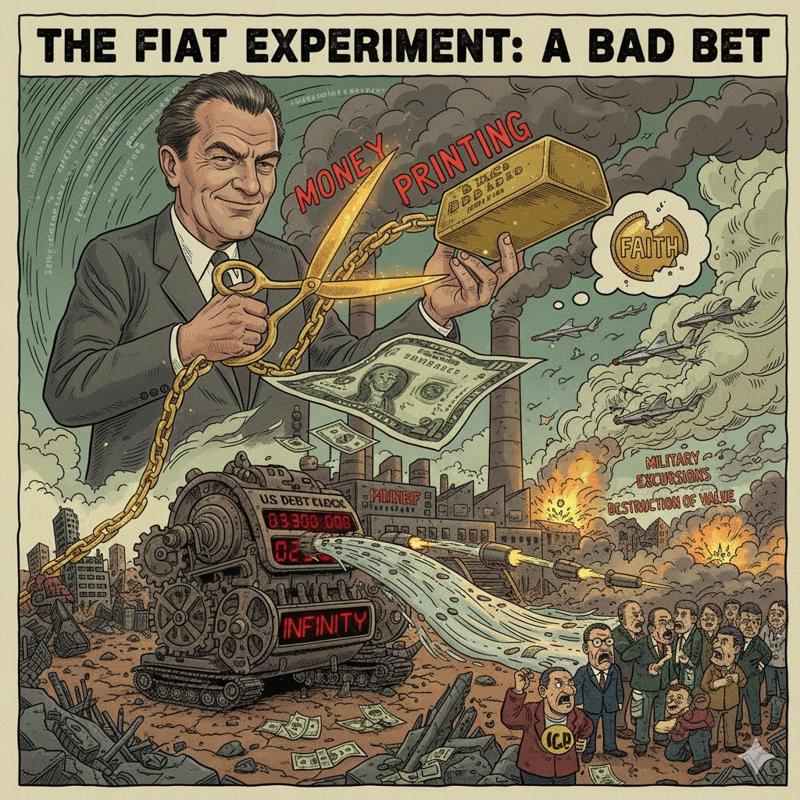

In the ultimate global economic rug-pull, Nixon famously severed dollar-to-gold convertibility in 1971, making the US dollar a pure "fiat currency," backed only by the "full faith and credit of the United States" (there's that word "faith" again), meaning the dollar's value depends entirely on trust in the U.S. government's ability to honor its monetary obligations. This has worked out ok for awhile, with global commerce conducted in dollars since the end of WWII, but now seems more and more like a bad bet, with the US debt clock ratcheting its way into the stratosphere as it is, with no obvious path to the growth required to service that debt.

This is much worse than gold. Whereas gold is at least real and relatively rare, fiat money is neither: it can be simply be printed (physically or digitally) by a central bank whenever they feel it is expedient to do so (which is at least partially a political decision, as opposed to one that necessarily creates any real value for society at large). This leads to overspending (i.e. bad investments), currency devaluation, and inflation, much to the chagrin of fiat holders, which is everyone.

It can also lead to dangerous outcomes. A giant sum of money is spent worldwide on ill-fated military excursions that not only don't create any new value, but indeed violently destroy it. Too much of this inexorably leads to currency collapse, not to mention immense human suffering. The thirst for power and control is insatiable, and the war machine can access the funds needed for its dirty deeds from the near infinite well of excess discretionary money printing, at least in the short term. A strong argument can be made that the freewheelin' fiat system is largely responsible for the preponderance of modern warfare [2].

The Fiat currency experiment

Sand dollars

Some other candidates on our continuing search for enduring value are:

art (whose value is almost completely subjective)

financial instruments that promise to deliver a return (with the attendant risk of... that not happening)

real estate, and

crypto

Bitcoin is a durable, fungible, easily transferrable, divisible, and provably scarce digital asset, which makes it an excellent potential store of value. Like gold, It's also permissionless, but it doesn't have gold's history of being accepted and used by most of the world, and so it still struggles with shared belief, as embodied by its price volatility.

What about a beachfront property in the tropics? We all want that sun-soaked, grass-skirted, piña colada experience. Surely that must be inherently valuable? Well, yes, but did you know that there was a time in the Cayman Islands where you could easily buy beachfront property because no-one thought it valuable? This was because hurricanes arriving on their shores each year could turn your newly built dream home into a pile of matchsticks. As a result, island authorities zoned cemeteries onto beachfront land, trusting that the dead wouldn't be disturbed by the howling winds.

Since then, hurricane-rated construction techniques and an ability to watch and predict storms from afar has made the prices of these rare beachfront lots go straight through their reinforced roofs. But climate change, with its even angrier tempests and penchant for reshaping shorelines may well reverse that trend again, the "ocean at your doorstep" taking on a whole new meaning.

Even without the fury of a category five, the gentle salty sea breeze you love also degrades your property over time, and cooling and maintenance costs continuously eat away at your investment. The winds of political change can also erase the value of your tropical getaway through annexation and nationalization, as Miami's Cuban "Golden Exiles" understand well. It seems that beachfront property is not exactly a slam dunk for long term value, either.

Manufacturing quintessence

Putting aside durability for a moment, it also seems "value" can be established on the basis of belief alone.

In a marketing coup de grace, De Beers famously breathed fire into the hearts of diamonds with their 1940s "a diamond is forever" ad campaign, claiming that the groom should spend "about 2 months salary" on each tiny rock as a lasting symbol and proof of their love and devotion. As ridiculous as this sounds, the idea stuck.

A renewed version of the 1940s "A diamond is forever" DeBeers ad

"Just Do it" (Nike), "Think Different" (Apple), "Finger Lickin' Good" (KFC) and "The Most Interesting Man in the World" (Dos Equis) are slogans that elevated their respective brands' value beyond the stratosphere.

Hermès, the producer of the world's most expensive handbag, props up the bag's price by restricting its availability to only those who have first purchased numerous ancillary scarves, jewels, and other items, proving their "bag worthiness" to the company. Shrouding the exact qualification criteria in mystery additionally makes people more willing to pay the untold thousands required to secure one.

We venerates the "masters" in the world of fine art—Picasso, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, etc —hoarding their works for proud display in museums and private collections. The importance of these artists' works within the historical context adds to their allure, as do narratives about their contribution to aesthetic innovation in their time. But I'd hazard that the current value of these pieces has more to do with the artists' fame, what they were last sold for, and the personal excitement of owning an original masterwork, than it does to do with the aesthetic value the buyer receives from gazing upon the canvas. Here, we look to experts in the tribe (auctioneers, historians, other buyers) to ascribe value, which we then dutifully accept and adopt.

The human factor

So what have we learned in this jaunt down the path to understanding value? Well... it seems that the whole affair is pretty iffy at best! If value can be manufactured with good marketing, and destroyed by prevailing circumstances, political forces, changes in psychology, or gusty winds, where do we hang our hat?

Maybe we need to abandon objectivity, and embrace the notion that value is purely and distinctively subjective, mysteriously emerging from the shifting cultural and tribal constructs dancing in our lizard brains. We evolved at a time when the resources we needed to survive were scarce, so perhaps it makes sense that we are highly attuned to value things we perceive as scarce, even if they don't directly help us to survive. We can't eat a bar of gold for breakfast, shelter ourselves in a handbag, or use bitcoin to entertain ourselves on a desert island. We can use these things as proxies for value, though, if we develop a shared belief about them with others.

The very fact that humans can rationalize value into existence—and that we can change our thinking or be led to think differently about what is valuable—is probably also a part of the answer to another disturbing modern value quandary: will human beings be valuable at all in a robot-dominated labour force?

Note that our internal urge to view ourselves as "good" and "valuable" regularly has us twisting and contorting in unpredictable ways to ensure that this proposition remains true in our minds, even with demonstrable evidence to the contrary. To wit: we continue to unleash a maelstrom of horrors upon the natural environment, even though we all know that it's essential for our very survival. Then we pat ourselves on the back because we replaced that incandescent bulb with an LED one last year, remember?!

Humanity is only "good" and life is only "valuable" because we (or our genes) have decided this by definition. But we can take this idea to the bank, so to speak... it's literally "as good as gold," since its tied up with our very identity, and is a persistently shared belief within the human family. We will continue to confidently proclaim this as a given, and reason forward from there, despite its somewhat faulty logical foundation.

In particular, the subject of my next (not yet written) article, "It all comes down to taste," rests squarely on this foundation. In it, I'll examine how "taste" will be the kingmaker in the modern workplace. Check back in a little bit for that one. Or subscribe (for free!) on substack to get notified when it drops.

———————————————————-

[1] for the software geeks among us, there is an analogue of The 5 Why's in the "Smalltalk" programming language. All computation is performed via message passing to objects, which then execute the corresponding methods, each of which is another series of message sends to other objects, each of which are themselves implemented by methods, mirroring the infinite whys. The curious will follow the message call chain until the bitter end, eventually arriving at a method like "+", which one sends to an instance of the class "Number" with another Number as an argument in order to compute their sum. However, the source code for the implementation of the "+" method simply reads "<primitive>." In other words, "you've reached the edge of the Smalltalk universe and must now just trust that the machine will add these two numbers for you and return the result." However, it won't tell you, hapless human, how it did that. Most unsatisfying.

[2] - It's definitely responsible for the ongoing, unfair transition of wealth from the lower to the upper classes (but that's the subject of another article)

———————————————————-

Podcast Music from #Uppbeat

https://uppbeat.io/t/abbynoise/burst-of-light

License code: CJFZZMXD0GXTYBDH