work

Feb 11, 2026

The Taste Deficit, Part I

The Role of Taste in Production

13 min

read

Summary

Human taste serves as a vital differentiator in commercial processes as AI automates output. Productivity belongs to robots, leaving humans to focus on the "wasteful" play and experimentation arising from our curiosity. Ultimately, humans will use AI as an amplifier, encoding their "golden intent" more and more to project themselves further into the world.

Image generated by deepai.org

If you started a business and didn't have to hire human beings, would you? With the advent of artificial intelligence, robots, and software automation, we all wonder what value human labour will have within the economy.

Some believe we are in the middle of a shift away from the productivity benchmark. In his article entitled "The Post-Productive economy" (Technium, January 1, 2013), Kevin Kelly succinctly lays down the essential context:

It’s hard to shoehorn some of the most important things we do in life into the category of “being productive.” Generally any task that can be measured by the metrics of productivity — output per hour — is a task we want automation to do. In short, productivity is for robots. Humans excel at wasting time, experimenting, playing, creating, and exploring. None of these fare well under the scrutiny of productivity. That is why science and art are so hard to fund. But they are also the foundation of long-term growth. Yet our notions of jobs, of work, of the economy don’t include a lot of space for wasting time, experimenting, playing, creating, and exploring.

— Kevin Kelly, “The Post-Productive Economy”

I'm not sure that he could have predicted just how much society would be up-ended by modern generative AI, but this is a remarkably germane observation for the modern age. Kelly proposes that if productivity is the central goal, humans beings are not the best tools. Instead, we are better at creative, experimental play, which underpins both art and science.

He also makes an implicit point about the nature of discovery in a commercial context. The electron was discovered by J. J. Thomson in 1897, but at the time had no practical use. Now, the modern world is completely underpinned by electronics, the economic value of which is vast and incalculable. Monet's "Impression, Sunrise" was panned by critics of his day, who dismissed it as "not even a finished painting," coining the (at the time, derisive) term "Impressionism." It has now become the canonical work of the time used to mark the birth of the Impressionist movement, in which artists moved from simply capturing reality to capturing how reality feels. This novel abstraction is said to have made possible all of modern art.

Impression, Sunrise (French: Impression, Soleil Levant), 1872, Claude Monet

Our exploratory impulses play an important role in discovery, eventually surfacing the very downstream opportunities required to commercialize them. For now, humans are still the creative force that sparks the engine of productivity, making us commercially important at least in that regard. Phew! But now you're wondering if AI will eventually also develop an affinity for play, exploration, and discovery, taking aim at the need for our creative sparks as well!

Let's stick a pin in that for the moment; it's the subject of part II.

From spark to substance

It should be noted that this kind of creative discovery manifests itself cyclically throughout commercial processes, not just at the outset, even though the inspiration that occurs during the conception phase is more obvious. The production process is also peppered with investigations, experiments, explorations, flashes of creativity, and intuitive decisions. Teams continuously improve the usability of their designs. Prototypes are created to prove out concepts and reduce risk. Curiosities are investigated and dark paths are dropped in favour of ones that show promise. Intuition is applied. Conception and production are both rife with endless gut-checking, nod-gathering, and exploration of the unknown.

We have a tendency to tout "productivity" as the essential difference-maker for the entire endeavour, but I'd argue that this tight cycle of incremental ideas and experimentation is just as important. Human intuitions based on the team's values, experience, cultural conditioning, and internally held purpose for the work are implicitly and repeatedly brought to bear. This is essentially an ongoing application of "taste": the continuous incarnation and integration of the subjective into a commercial product or service.

Taste is an emergent property of everything you are: all that you've ever pondered, experienced, avoided, lamented, celebrated, learned, yearned for, or struggled through. There is also the collaborative aspect of taste within a work environment: that unpredictable chemistry of different human perspectives colliding. Taste infuses our work with uniqueness, scarcity, and innumerable aesthetic propositions which, as we saw in the last article, all generate a sense of value.

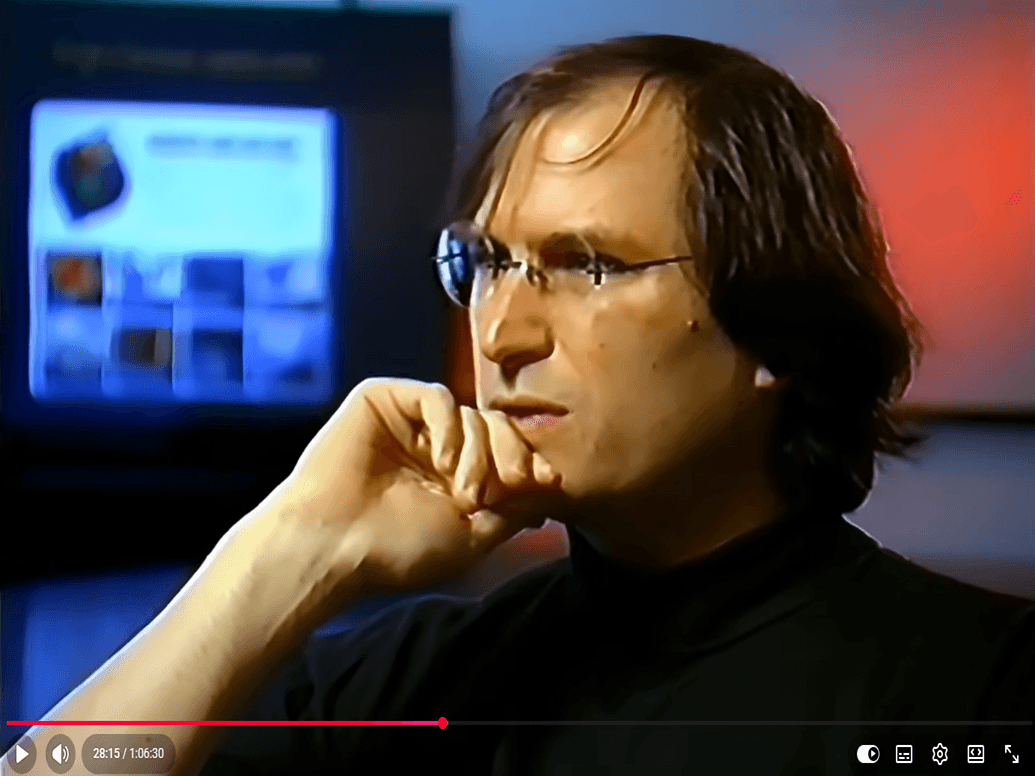

In the 1995 "lost interview" by American journalist Robert Cringely for the PBS Documentary Triumph of the Nerds, Steve Jobs claimed that a focus on "content," as opposed to the institutional "process" of production, is what makes for great products.

People get confused. Companies get confused. When they start getting bigger, they want to replicate their initial success. And a lot of them think, “Well, somehow there is some magic in the process of how that success was created.” So they start to try to institutionalize process across the company. And before very long, people get very confused that the process is the content. And that’s, ultimately, the downfall of IBM. IBM has the best process people in the world. They just forgot about the content.

And that’s what happened a little bit at Apple, too. We had a lot of people who were great at management process. They just didn’t have a clue as to the content. And in my career, I found that the best people, you know, are the ones that really understand the content, and they’re a pain in the butt to manage, you know? But you put up with it because they’re so great at the content. And that’s what makes great products. It’s not process. It’s content.

— Steve Jobs, The "Lost Interview", time=28:15, 1995

In the same interview, Jobs also proposes that the "magic" of a great product originates mostly from this meandering experimentation within the product's conceptual and physical architecture, as opposed to simply following on predictably from the initial creative "spark."

You know... one of the things that really hurt Apple was after I left, John Sculley got a very serious disease, and that disease... I’ve seen other people get it, too. It’s the disease of thinking that a really great idea is 90% of the work, and that if you just tell all these other people, you know “Here is this great idea,” then, of course, they can go off and make it happen. And the problem with that is that there is just a tremendous amount of craftsmanship in between a great idea and a great product. And as you evolve that great idea, it changes and grows. It never comes out like it starts because you learn a lot more as you get into the subtleties of it, and you also find there is tremendous trade-offs that you have to make. I mean, you know, There are just certain things you can’t make electrons do. There are certain things you can’t make plastic do or glass do or factories do or robots do. And as you get into all these things, designing a product is keeping 5,000 things in your brain, these concepts, and fitting them all together and kind of... continuing to push… to fit them together in new and different ways to get what you want. And every day you discover something new, that is a new problem or a new opportunity to fit these things together a little differently. And it’s that process that is the magic.

— Steve Jobs, The "Lost Interview", time=32:38, 1995

Here, what Jobs calls "content" is the wide expanse of interacting concepts and components comprising the thing you're building. Great content requires an unflinching commitment to the product vision in order that the multitude of problems and constraints throughout production can be navigated. The result is a reflection of the love, care, and understanding given by the makers of the product. The process resists standardization and systematization by its very nature.

Compressing the taste loop

Peering into the future, as we learn to integrate and use AI tools, I believe we'll see the importance of taste rising concurrently with the increased productivity made possible by AI and automation. In fact, at a micro level, it will shrink the time between the point at which we give an AI companion any instruction, and the point at which we evaluate its output, potentially redirecting it where it doesn't match our expectations or intent. The increased productivity made possible by AI will compress the iterative cycle of experimentation, and accelerate the onset of opportunities to express our taste. In the limit, humans become wholly and exclusively responsible for evaluating output and adjusting the delivery trajectory based on taste.

The limiting factor on the speed at which products are produced will be how fast we can orchestrate AI to speed production, and how fast we can apply these subjective judgements to the overall production process. And the limiting factor with respect to the overall quality and value of the product to the market will be a reflection of the "quality" of those intuitions and judgments. The value of the intervening production effort will decrease over time as it becomes faster, more automated, and inexpensive.

To the extent that taste is a feature of humanity, these examples hint at why it may be resistant to automation. Indeed, our taste may end up being amplified by AI, rather than replaced by it, just as a guitar amp doesn't replace a musician's artistry but projects it more powerfully. Someone with great visual taste but poor technical skills could use AI to execute their vision. Someone with brilliant product ideas but weak marketing instincts could have AI handle social media execution while they focus on the creative direction. Bad taste will also be amplified, but the market will cull this output from the herd.

The rarity conundrum

As we saw in the last article, human beings value effort and rarity. I recall the subjective experience in the 1980s of hunting around for CDs of my favourite bands. I'd learn about an album, save up 3-4 weeks worth of allowance, trek to the record store each week to try to find it, bring it home to sit with the cover art and liner notes while I listened, and tell my friends about the whole experience. This has been replaced by a much less valuable feeling of "I can listen to any song at any time wherever I sit," but… when was the last time you delighted in the experience of listening to a whole album?

I also remember being completely mesmerized by my dad's home slideshows. We'd only get two or three rolls of 24 Kodachrome developed each year for our carousel slide projector, but you couldn't contain my delight whenever I saw my young self and my family projected up onto our darkened den wall. It was magical! Now, my family takes thousands of pictures each year and never looks at them.

Similarly, each new mountain of AI slop immediately devalues its own content, despite the fact that any given piece may be useful or interesting in its own right. AI can produce millions of articles in the time it takes me to produce one, but knowing this, would anyone want to read them? And besides the sheer effort required to do so, the "moment of connection" we have with human authors would be sorely missing, since we can't project ourselves into shoes of the artist: we implicitly know that human beings can't possibly be that productive, so the output becomes less interesting. Also, the Uncanny Valley still applies to most AI-generated content, further marginalizing it.

Over time we will devalue the productive capacity of AI, ironically owing to its very prodigiousness, and instead cleave to the creative magic of human authorship, and other relatively rare or novel aspects of production. We'll also appreciate the effort and aesthetic choices required to sift through the noise to unearth signal, like a silky DJ spinning a deep cut. Audiences will value human authorship and expert curation, and on the whole, creators will serve them in their work.

Prompt stars

ChatGPT popularized the prompt/response interface when it was released, and since then, more capable models have emerged weekly, each with more parameters, more extensive training on larger data sets, multi-modality, and bigger context windows to improve the continuity of discourse. LLMs are redlining tokens like a formula one rocket.

The length and complexity of our prompts have also been rising in lockstep. Predictably, better-formed, more thoughtful prompts (for any language model) return more nuanced, relevant, and useful results, suggesting that an ability to do this well might be where all the value sits in future knowledge work.

A while back, the internet had prematurely proclaimed that "Prompt Engineer" would soar to the upper rungs of the salary ladder, which it did for about 17 nanoseconds. But now, access to AI tools is pretty ubiquitous, and workers of all stripes are improving their familiarity and facility with them. Industry-specific experts additionally have domain and systems knowledge, giving them an advantage over generic "prompt engineers." For example, doctors will perform better than most at medical prompt-diagnostics. Lawyers will be the best prompt-drafters and prompt-shapers of legal arguments. And software developers will become expert prompt-code-generators.

All of these experts will direct AI, evaluate output, and redirect it using their perspective, expertise, and taste. It turns out that a "prompt engineer" is just an abstraction of the concept of "expert prompter in my field." Workers will be expected to pair domain knowledge with their own experience and judgement, and understand how to drive AI to deliver the most value. As luck would have it, there will not be one "prompt engineer" to rule them all.

Sorry Sauron. We'll all develop prompting expertise.

As prompts become more elaborate, increasingly we will need better systems to manage the burgeoning libraries of our "Glengarry prompts" — those gems that we update and re-use on a regular basis to prime the LLMs for "better performance." We'll also need an ability to update the context as our taste or vision changes. And if we start to view context as a representation of personal value in a commercial setting, then we'll need tools to protect our context files from misappropriation, along with other vectors of exploitation.

Software developers and business analysts may be better at this than anyone else. Their jobs largely consist of deconstructing the intentions laid out in a requirements specifications, translating them into code, and inoculating those systems against novice users and bad actors. In a sense, they convert a less precise English specification into a more precise code specification, from which working programs are then generated and secured. The precision of expressed intent required for good code mirrors the precision of expressed intent needed for a good prompt.

Developers also have to prepare and respond to every potential runtime eventuality, no matter how remote its chances of occurring. This is structurally embodied within the branch points and exception handling keywords scattered throughout code. When product owners say "<thing x> will never happen," the standard developer retort is "yeah, but what if it does?" This is because they need to put something after the "else" statement or into the exception catch block[1]. A lifetime of deconstructing intent, organizing and expressing it precisely in code, and ensuring code completeness has primed developers to become the star prompters of our time.

Manifesto as infrastructure

Developers also don't like to repeat themselves in code or otherwise (the "DRY" principle). They've already figured out how to take all of their favourite prompts and re-use them as an aggregate expression of their "golden intent" across all of their projects. More and more, this intent is collected within "context files" in their AI workspaces, the "markdown" format ascending to the lingua franca for expressing it. This includes the evolving product vision and goals, the architectural constraints, the UX design system specs, the preferred technical design patterns, coding standards, runtime performance criteria, roadmap, and expressions of known technical debt — all written in English (or other human language) as opposed to code.

Together, this shared context guides all of the future prompts used to evolve the system at any point in its lifecycle, including those used at the start when nothing is yet built. The context files are at once an expression of the taste and shared intent of the joint product development team.

In no time at all, the obsessive among them took this to the extreme, using gigantic markdown files to painstakingly notate not just their preferences, but everything they had learned about good design, development, and testing over the course of their careers, serving this to the LLMs as initial inference context before the product brief even makes an appearance.

Here's an example of a large software development context file for the Claude LLM. While extensive, it's by no means complete, nor can it be considered to be "correct," since that's largely a subjective determination. There are an infinite number of distinct solutions that correctly satisfy product requirements, each taking different paths to get there. Digital holy wars are fought over the subject of "which way is best" and why, mirroring the polarization of modern political discourse. Nevertheless, these context files are an attempt at a full expression of the very aesthetics of the prompter in question. Each developer has their own notion of "what good looks like." When everyone has access to the models, taste, as expressed in markdown, is what makes one team's product different from that of another. I wouldn't be surprised if the contents of your "taste" files eventually became one of your differentiators as a job seeker.

Context in the limit

This doesn't just apply to software development. The best among us in any field will be both opinionated about their taste, and able to express it in way that AI agents can understand and digest. Agents will deliver the productive capacity in service of realizing that intent.

The fulsome externalization of "taste" within context files has the potential to make digital twins more compelling and valuable to their human counterparts. The goal would be to understand you and approximate what you would do in any novel situation, allowing you to project yourself more fully into the world.

Digital twins could perform large scale opportunity matching (jobs, experiences, dates), curating the world on our behalf according to our preferences. They could allow us to delegate higher level tasks to be performed "in our own voice." Indeed, an AI that "understands" us can help us to "rubber duck" our own mindset, tackle our neuroses, and probe the landscape of our nascent ideas and intuitions for signal. It will likely be important to closely guard access to these files. Improper access might subject us to advertiser targeting, social marginalization, or political persecution.

Focusing on the positive, consider this: healthy democracies require informed participation, but we can't expect citizens to internalize and digest the complex inputs required to cast an informed vote on every individual issue that may affect us, hence the need for a representative to cast votes on our behalf. But representative democracies are subject to corrupting forces. A digital twin might indeed make direct democracy possible, reading our context files and recommending (or even voting!) according to our taste and values after sifting through and evaluating the text of each proposed bill.

Taste is a vital differentiator in commercial processes today, and will become even more vital as AI automates production. In part II of this series, we'll discuss the difficulties of removing ourselves completely from the taste loop.

————————————————————————————————

Footnotes

[1] A typical construct for exception handling within code looks something like this:

try {

somethingINeedToDo()

} catch(SomethingWentHorriblyWrongException) {

recoverFromThat() // developers need to put something useful here

}

————————————————————————————————

Podcast Music from #Uppbeat

https://uppbeat.io/t/

License code: